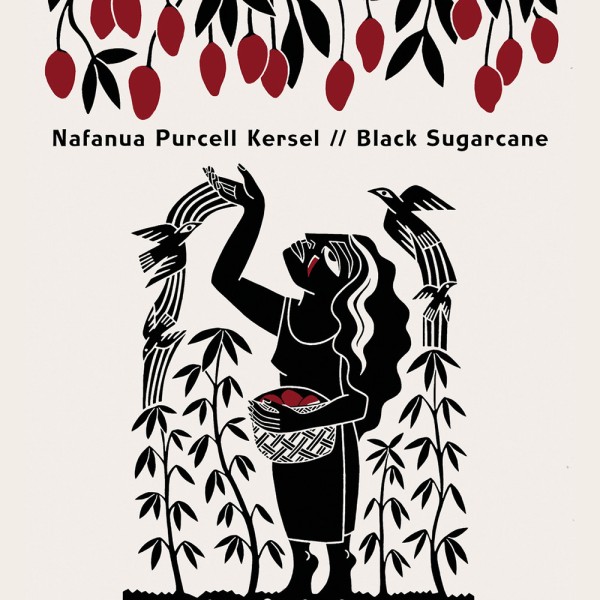

Sight Lines: Women and Art in Aotearoa

Written by: Kirsty Baker

Auckland University Press

Reviewed by: Jo Lucre

It’s hard not to be impressed by Kirsty Baker’s Sight Lines: Women and Art in Aotearoa. With its lofty heftiness and fabric cover, it’s a work of art even before the first page’s turn.

What Baker has compiled is a stunning account of the extraordinary creative genius of women across Aotearoa: those who have come before and those who continue to create in contemporary times.

Not limited to one genre, Baker offers an almost panoramic view of an art history constructed by women that – though not exhaustive by the author’s own admission – spans mediums and decades, from curators and photographers to sculptors, poets, and writers to name just a few.

What’s interesting is how Baker has brought the artists’ collective and individual voices to the fore, their words as fluid and engaging as the art they have created. Through images and essays, their storytelling is reflective and impactful. The book covers the influences, history, and connections to time, place, and space that have informed the artists’ work. Political, cultural, societal, and gendered contexts wind, thread, and integrate like branches through both the narrative and the art, sometimes subtle, sometimes profound.

I found artist Yuki Kihara’s work Quarantine Islands interesting. Much of it focuses on challenging societal norms and concepts. Through a series of lenticular photographs made during the global pandemic, Kihara speaks to the themes of isolation, contagion, and quarantine. It’s like the present meets the past. “The series of work follows a long history of human confinement across the land and ocean that she pictures”, Baker writes.

This collective and collaborative account from Baker and contributing writers is nuanced, interesting, and bold, told through the eyes of women. I thoroughly enjoyed this striking collection and I’m sure it will resonate with many art enthusiasts.