The Brief and Frightening Reign of Phil

Book by Tim Price

Directed by: Lyndsey Turner

Shed 6, 10th Mar 2020

Reviewed by: Madelaine Empson

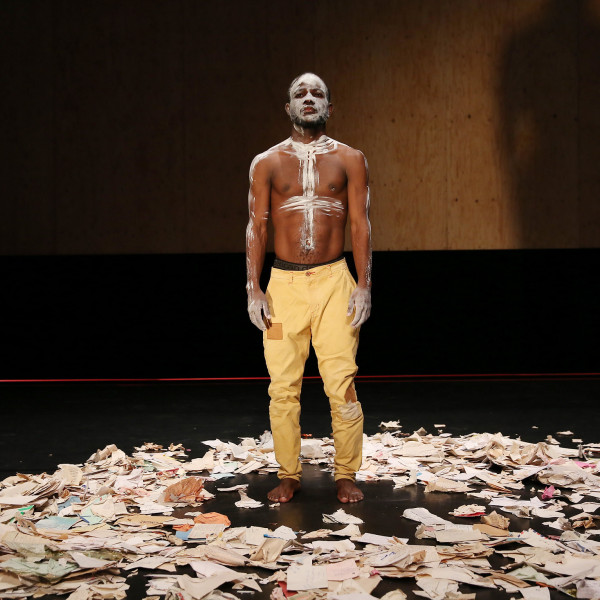

Based on the George Saunders novella, The Brief and Frightening Reign of Phil is set in a country divided in two by fear and misunderstanding. Only five people live in tiny Inner Horner. Outer Horner is large and in charge, and worst of all, Phil (Daniel Rigby) lives there. When an earthquake shrinks Inner Horner, its residents must occupy the neighbouring territory. Phil decides to tax them, but they don’t have any money. How far will he go to see the debt paid?

With music and lyrics by Bret McKenzie, there’s a distinctly Flight of the Conchords feel to this production. Actor Andrew Paterson nails a lot of the nuance required to hit this unique style of Kiwi comedy home. The whole cast delivers, and many of them shine brightest in song.

Nigel Collins brings a tear to the eye with a sweet and sensitive lullaby to his character’s son. Naana Agyei-Ampadu’s sorrowful ballad brings the house down, Jeff Kingsford Brown’s presidential twirl is a sheer delight, and Tom Knowles causes shrieks of laughter with a toe-tapping country song that proves McKenzie’s extraordinary compositional range. Devon Neiman’s seduction song is the highlight of the show, if not the year, so far.

While Rigby brings a hilarious Matt Berry feel to the role of Phil, his final moments onstage are as powerful and frightening as his character’s brief reign of terror.

The introduction of the fraught mother-daughter relationship between Freeda (Vanessa Stacey) and Gertrude (Caitlin Drake) is the only place the script veers from excellence, with the flimsy storyline left unresolved.

The Brief and Frightening Reign of Phil is wickedly funny and breathtakingly relevant. The level of professionalism and polish on display makes it easy to forget this is a work-in-progress showing. Currently in its first draft stages at the National Theatre in London, I would pay to see it on the big stage just as it is, scripts and all.