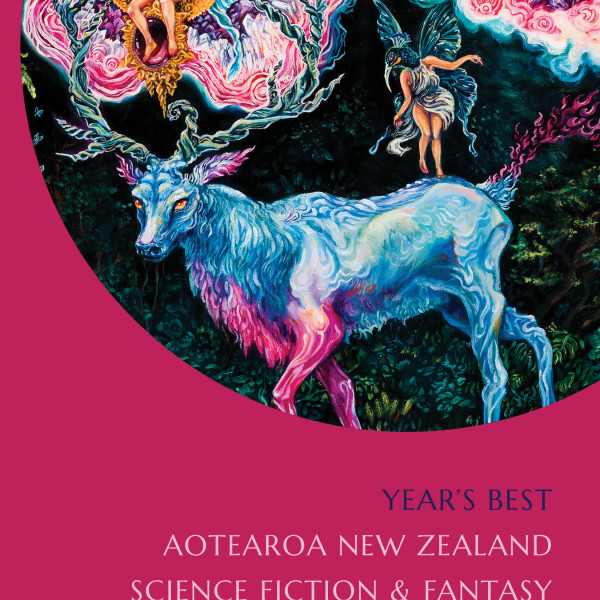

Year’s Best Aotearoa New Zealand Science Fiction & Fantasy Volume IV

Edited by Emily Brill-Holland

Paper Road Press

Reviewed by: Courtney Rose Brown

Men flicker out like photos burned. Folklore fuses with our everydays. Birds no longer sing in cities. Year’s Best Aotearoa New Zealand Science Fiction & Fantasy Volume IV is a beautifully curated collection of our country’s best science fiction and fantasy short stories. These are stories that you can enjoy on their own, picking up whenever you feel like a little literary snack, or it can be a whole meal that you devour in one sitting.

The volume begins strong with I Will Teach You Magic by Andi C. Buchanan. Buchanan’s story tucks you in with a spell of love woven into the ink. It stretches out of the pages, onto your fingers, and flows into your heart. It’s the perfect beginning to the collection like sitting around a campfire, hearing stories retold that have been passed down by generations.

Plague Year by Anuja Mitra skilfully spins an ever-so-relevant social commentary by playing within the familiarity of a classic folklore. Data Migration by Melanie Harding-Shaw is a beautifully crafted tragic glimpse into a reality that just may fall upon us. A stark reminder that regardless of whatever challenges we face, teachers are forever the glue of civilisation, building hope and light within new generations. Interview with Sole Refugee from the A303 Incident by James Rowland is an incredibly gripping short story that you don’t want to end. The only survivor walks on past all the pain, fuelled by the pressure to meet deadlines at work.

Because this is a collection of stories, there isn’t enough space in this review to address each of them. I absolutely recommend this gem of a book. Standouts in the volume were stories that lingered on the precipice of our realities but held enough distance to gain perspective. Voices are taken, time is stolen, and worlds crumble as we watch frozen as witnesses. The volume holds the magic of many voices that all should be heard.