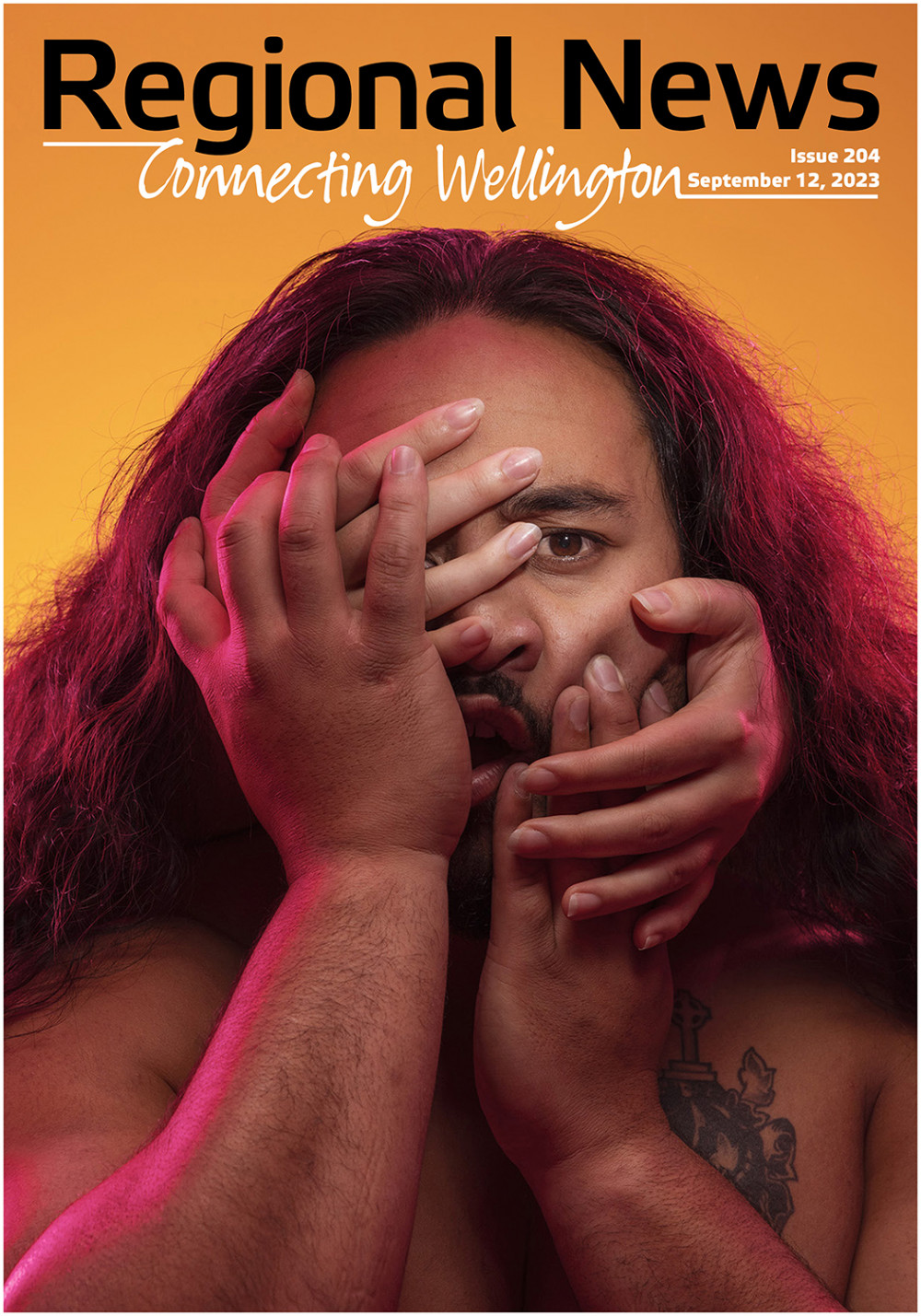

The Little Ache – a German notebook

Written by: Ian Wedde

Victoria University Press

Reviewed by: Margaret Austin

Appreciation of poetry closely resembles appreciation of painting – it’s highly subjective. So in commenting on Ian Wedde’s latest collection, I find I must put aside my preference for poems that rhyme and ones that address contemporary themes.

A dictionary definition of poetry runs: “a literary composition that is given intensity by attention to diction (choice and use of words), sometimes involving rhyme, rhythm and imagery.”

Note that this definition makes no mention of content. And it’s content, for my two cents’ worth, where Wedde scores most points. For his exhaustive collection (76 poems) largely charts his family history back to the 1700s: “stalking the family ghosts of German ancestors and obscure relatives and associates”, as he puts it.

A Creative New Zealand Berlin Writer’s Residency 2013-14 provided the opportunity for keeping a diary, and it’s from that diary Wedde draws his material.

His forebears merit such a poetic celebration. Some of them witnessed a great deal of what they probably didn’t want to witness, giving rise to serious themes. And a relative-of-a-relative of some kind published a mostly unread panegyric to the Paris Commune martyrs – now you can’t get more esoteric than that.

The chief enjoyment for me was on the linguistic side – the words and imagery Wedde uses. I loved the pigeon named Werther “fastidiously poking feathers into an improbable nest”, enjoyed the extended metaphor of the bowl of pea soup, and accurately pictured “the narcissist of small differences” encountered at the library when Wedde is enquiring after a relative’s book. On a grimmer note, there’s the watering can in the Stasi Museum, and “the implacable conduit where Arendt disciplined her bafflement into thought”. The little ache of the title merits a poem of its own.

It’s a scholarly read, but there’s much deserving of reflectiveness for the general reader – and a bonus for those who are familiar with German in the form of a generous smattering of words and phrases in the original tongue.